Tag: interview

Olivia Colman knows what she’s doing, even when she doesn’t

Olivia Colman knows what she’s doing. Even when she doesn’t, she does.

“I think just time passing gives me a bit more, you know, confidence,” Colman tells Esquire Middle East.

The English actress, 47, has in the last decade gone from one of the most underappreciated talents in the world to one of the most universally beloved, collecting an Academy Award for Best Actress, four BAFTAs, three Golden Globes and a Screen Actors Guild award.

On top of that, she’s nominated for another Academy Award this year, too—for her role in Florian Zeller’s The Father, opposite fellow nominee Anthony Hopkins.

Colman is one of the rare individuals who, no matter how many accolades you bestow upon them, never seems to be changed by it all in the slightest. Talking to us over Zoom, she’s as genial and open-hearted as ever, someone who you can’t talk to without feeling like you’ve made a new friend.

The secret to her success—and her unbridled warmth and aforementioned confidence—is in her acceptance that you don’t need to be perfect to be great.

“I know what I’m doing now. Well, you never get to the point where you really feel like you know what you’re doing. But I trust myself, all because I know I can make mistakes. I think that helps. I trust that if I make a mistake, it doesn’t matter,” says Colman.

The actress, who famously has no process in how she gets into characters, performed nearly automatically opposite Hopkins in the Father, a harrowing portrayal of one man’s failing mind and the daughter he’s relying on to cling to man he once was, and can’t accept he no longer is.

The two worked without rehearsals, sparring back and forth in one or two takes and then laughing off the screen. All of this was enabled by a first-time filmmaker in Zeller who trusted his actors and allowed them the space to create without the preciousness or stress that often comes with inexperience.

That, to Colman, was everything.

“I think it’s so important to feel safe and secure. Anyone who tries to sort of break you down and make you feel absolute nonsense. If you feel safe and secure, and you trust everyone around you, you can go anywhere with any amount of emotion,” Colman says.

“If you get someone who’s an a**hole, you don’t want to be nice. You don’t want to do good work for them.”

Rufus Sewell, who plays Colman’s increasingly less-patient husband, took to the vibe that Zeller, Colman and Hopkins had created on set immediately.

“I’m not a particularly serious person. When people meet me, they’re often surprised because I always get cast as these dour, humourless tw*ts,” says Sewell.

Colman brought out the silly in Sewell like few had before.

“It was very fun, easy, and especially silly. There was a lot of silliness. With me and Olivia, I felt like that we were going to be separated. That was the joy of it. I looked forward to each day,” says Sewell.

Colman, Sewell and Hopkins would eat together each day, getting a laugh out of one another hours on end.

“There were no dressing rooms or trailers. Most of the time we were in the same makeup room telling stories and jokes and, you know, farting around. For me, it was a wonderful discovery that my favourite actors work the same way I do,” says Sewell.

At the end of the day, of course, what matters most is the work itself, and in The Father, the crew has turned in a masterpiece—a wholly unique, horrifying and tightly-wound drama that deserves every one of the six Academy Awards its nominated for, including Best Picture.

The specialness of The Father, of course, is not lost on any of them, least of all Colman herself.

“I know that I had no problem getting out of bed every morning. No, I was excited to go to work. I thought I’m part of something really beautiful and I’m working with lovely people. I love my work. I love working. I love going to work. But every now and then you get one that’s really special, and this felt special. I’ll be eternally grateful to Florian for writing it and letting me be in it and letting me act opposite Anthony Hopkins. I can die happy now that that’s happened,” says Colman.

The Father is in theaters now across The Middle East

Source: esquireme.com – Olivia Colman knows what she’s doing, even when she doesn’t

The Secrets to Olivia Colman and Helena Bonham Carter’s Transformation for ‘The Crown’

The Crown is back! The drama series, which follows the life of Queen Elizabeth II, comes back on November 17th on Netflix, with lots of news – including the planned changes in the cast. Claire Foy, who garnered significant acclaim for playing Elizabeth in her early years on the throne, leaves the post for Olivia Colman, who won the 2019 Best Actress Oscar for playing a different queen (Anne) in The Favourite and was a recent Emmy nominee for her role in Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s comedy Fleabag.

In season three, which focuses on 1964-1977, Queen Elizabeth II (Olivia Colman) and her family struggle to meet the challenges of a rapidly changing Britain. From cold war paranoia to the jet-set and space-age, the season follows the royals as they navigate the flamboyance of the swinging ’60s and the long hangover of the 1970s. Ever-present is the need to adapt to a new world, more liberated but also more turbulent.

On the show, Olivia Colman’s similarities to Queen Elizabeth are striking, as are those of Helena Bonham Carter to Princess Margaret. To uncover the secrets behind these transformations, L’Officiel spoke to Cate Hall, the makeup and hair designer for the series.

(Photos: Disclosure)

What was your initial reaction when you were called to work on this third season of The Crown?

It was obviously a dream come true. It’s the kind of thing I’ve always wanted to do, especially with reference to historical periods and with characters so real that they were part of contemporary British history. But I joined in to replace Ivana Primorac, which is incredible but also comes with a lot of pressure and anxiety.

What is the research, preparation, and attention to detail like in order to create the looks of the series? What was it like to dive into that?

I am very thorough with work and have always been a fan of The Crown just for that. So for me, actually, research is part of who I am and what I like to do. I had just had a baby, so I was on maternity leave and spent four months working part-time. The research was done while breastfeeding all night, so it was kind of crazy in the world of The Crown.

And specifically with Olivia’s work to become the queen in such a striking look…can you tell us how it went?

The most iconic element we know of the queen is the shape of her hair, which hasn’t changed for sixty years. So the most important thing was to establish the hair shape for the 1960s. The wig contains at least three or four different colors of real human hair, made by Alex Rouse. We had to take a lot of weight out of our hair to give it a kind of lightness over the previous period, because part of the character’s achievement is not just the obvious type, it’s the queen, but it’s how the queen behaved from 1964 to 1977 with as few fake devices as possible.

(Photos: Disclosure)

Now, talking about the wigs and their variety, are different wigs worn for different occasions, even for the same character, or are they the same?

We have repeated wigs for all the main characters because we depend so much on the schedule of the day. Sometimes the scene is rainy, and the wig is wet. To get it back takes time, so we always have some extra ones.

And roughly how many wigs would you say you worked on for this third season?

I did the math here and I think it was about 47. And that includes repeated wigs and partial wigs for backup terms.

What about Princess Margaret. How did you create her hair and style compared to Elizabeth?

Her hair and makeup really relate very well to the narrative in terms of her characters. Elizabeth is all about consistency, sameness, and reliability, and basically her hairstyle doesn’t really change. The type of development and change is very subtle. While Margaret was in fashion, she followed the arts and culture and changed her hairstyle and makeup regularly. So we were able to approach Helena’s character with a little more versatility and a little more variety.

(Photos: Disclosure)

How was it for you to work with Olivia Colman and create this new Elizabeth?

Magic! Olivia is extremely instinctive in her acting and she had absolute confidence in my work. To Olivia, it seems that this moment of makeup and hair is very valuable as a process for her to get into character.

And was Helena Bonham Carter like that too?

No. Helena is a very different actress. And it’s interesting because it’s fascinating, it’s one of the unique privileges of our role: watching actors transform into their characters. Helena had many opinions and ideas of things to try because she loves to get involved in everything. Margaret goes through a lot at this time and Helena was excited to transform, to test contact lenses, to test different wigs.

Is there any makeup, hair, or overall look that you are most proud of this third season?

Several! But I’m really proud of how Olivia has aged very subtly from beginning to end of the season. Suddenly, she is this much more mature queen in the 1970s.

(Photos: Disclosure)

(Photos: Disclosure)

Queen of the Screen: Olivia Colman on fame, fortune and The Crown

Oscar-winning actresses, like royalty, normally require a certain protocol. There will be the entourage to manage, the punishing schedule to work around and a long wait before one is ushered into the Presence with a list of pre-vetted questions. Having spent most of the previous day immersing myself in an intriguing, very early cut of The Crown‘s third season, in which Olivia Colman steps into the Queen’s sensible pumps, I am expecting her to be a daunting combination of both Hollywood and Windsor. As a result, I almost miss her when she slides shyly into the foyer of the Ham Yard Hotel, a few minutes early, alone, and anonymous in jeans and trainers. ‘Oh gosh, I’m not wearing any make-up,’ she says, apologetically, when I introduce myself. ‘I thought I’d get here in time to put some on!’

Perhaps it isn’t so surprising that I don’t recognise her at first. Colman’s ability to embody different roles is unsurpassed, her range extraordinary. Having made the nation howl with laughter in Peep Show and Rev, she traumatised us with searing performances in ITV’s drama Broadchurch and the 2011 film Tyrannosaur, while the passive-aggressive stepmother she portrays in Fleabag somehow causes you to inhabit both states – laughter and distress– simultaneously. How does she do it?

‘The fierceness, the sadness, the darkness and despair that emerge in her work seem to issue from some other source, and make her gorgeous talent, whether it draws from real or imagined pain, undeniable,’ declares Meryl Streep, her co-star in The Iron Lady, when I email to ask. ‘I think she is one of our GREAT actresses, I felt so lucky to have worked with her; and I can’t wait to see where that antic, brave imagination takes us with the Queen. Because it will be imagined, as there is no more private, and hence mysterious, personage than Queen Elizabeth. But I am sure Olivia will lead with her heart and be guided by her unerring intuition and intelligence – and draw as accurate an essence as can be divined.’

While Colman put on more than two stone to play Queen Anne in The Favourite, the part for which she won her Academy Award for Best Actress this year, her genius is less to be found in imitating a character’s physicality and mannerisms than in mining their inner emotions. ‘The joy of playing that part was I got to be almost 15 people in one. Such extremes! That was so much fun!’

By contrast, I expect that her new role playing our current monarch, while highly anticipated by Streep and the rest of us, may well be the toughest of her career.

‘I don’t really enjoy research,’ Colman admits, as we chat over breakfast on the hotel’s roof terrace. ‘But for this, I have to accept it. I can’t just sit like me, I have to sit like her, and look like pictures of her. They have been teaching me how to walk – I’m really terrible at that, I have no physical awareness. I walk a bit like a farmer, one of the directors said.’

The voice was another challenge. ‘I thought that general“posh” would do it, but apparently not. Really unusual vowel sounds,’ she says. Like what? ‘Well, it’s not quite this, but if you’re saying “yes”, you say “ears”.’ She bursts out laughing. ‘It’s fun to do, isn’t it? Very hard to stop. Ears.’

Still harder for her, I would imagine, was perfecting the Queen’s all-but-unshakeable imperturbability, so beautifully embodied by Claire Foy, that offers barely a hint at the passions that maybe raging beneath. Colman, by contrast, seems to be lacking a protective layer of skin that has been granted to the rest of us. It is what makes her so compelling to watch on screen – you can see the emotions chase each other in succession across her mobile features – but can she play blank? ‘Claire was so brilliant at it that for the first few months, I just thought, “What would she do?” and I did that,’ agrees Colman, humbly. ‘I’m not very good at not moving my face.

‘There’s one episode where they tell the story of Aberfan –which, shamefully, I didn’t know – and it was so awful, tragic and harrowing, and I really struggled with it.’ (In 1966, a colliery spoil tip slid down a mountain onto a primary school in the Welsh village of Aberfan, killing 116 children and 28 adults. Famously, this appalling tragedy elicited one of the Queen’s rare public missteps, when she refused to visit for eight days, giving rise to public criticism. In 2002, she admitted that this was her ‘biggest regret’.)

‘So they gave me an earpiece and put on the Shipping Forecast and I just listened to that and pretended that was all that was going on,’ says Colman. Even so, watching the episode in question, I could clearly see her eyes welling up.

Colman’s middle-period Queen has fewer of the grand set-pieces of Foy’s reign – much of the drama and glamour goes to Princess Margaret, played by Helena Bonham Carter, who cavorts on Mustique with Roddy Llewellyn while her sister grapples with drearier issues such as Churchill’s funeral, Prince Philip’s mid-life crisis, Wilson’s resignation, the rise of Margaret Thatcher and the Falklands War… a period the monarch herself might have termed a ‘tempus horribilis’, perhaps?

Ironically, Colman’s own existence is a good deal more glamorous by comparison, right now at least, following her Oscar win this year. ‘I can’t register that it’s happened – it’s bonkers!’ she says, laughing in disbelief. ‘It’s in our sitting-room, on the sideboard, and we keep laughing at it. It looks fake, it’s so shiny. And it’s really heavy! I could do some amazing weightlifts.’

Watching again the moment when she was proclaimed the winner, I note with interest that she seems almost appalled to hear her name read out. ‘I was terrified, because I was going to have to say something in front of all these people,’ she acknowledges. ‘Ed [her husband] sent me a text saying, “Please, just think of these points,”but I was like, “It’s not going to happen, Eddie.” It feels unlucky to prepare something.’ Who did she expect to win? ‘Glenn Close. She was sitting right in the middle, wearing gold, so I thought she must know something.’ Prepared or not, Colman’s spontaneous, witty address was one of the highlights of the night, as, breathless and seemingly on the verge of tears, she sang the praises of her co-stars Rachel Weisz and Emma Stone– ‘the two loveliest women in the world to fall in love with’ – and then blew a raspberry at the continuity person telling her to wrap it up. She also declared that, even while she was working as a cleaner to make ends meet, she had dreamt of such a moment. ‘Everybody does, don’t they?’ she asks. ‘A bit?’

Born Sarah Olivia Colman, the daughter of a nurse and a chartered surveyor, she had a happy childhood in north Norfolk – itself, of course, a favourite Windsor stamping ground. ‘Well, they never came round our house,’ she jokes. She went to a girls’ school in Norwich, where she discovered her love for acting playing the title role in a production of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. ‘I was so shit at everything at school, but I did the play and thought, “Oh, I like this!” I actually had the urge to do the homework and learn the lines,’ she says. ‘I was quite a jolly kid, but not particularly confident, and suddenly being someone else was amazing. And I could do things as someone else that I could never have done as myself. But I didn’t know if I was allowed to be an actor. Nobody knew how to be in that world.’

Instead, she decided to apply to a teacher-training college inCambridge, and acted in university productions alongside David Mitchell and Robert Webb, who became her close friends. Realising that teaching would never be her métier, she supported herself working as a cleaner – ‘the job satisfaction was amazing!’ she declares with sincerity – and continued to perform, eventually winning a place at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School. In her final term there, she was asked to attend an audition for a TV show, and arrived to find Mitchell and Webb waiting for her. ‘And then, they were basically responsible for all my work for years…’ she says.

This bouncy summary suggests that Colman’s rise to fame was unclouded by any of the issues highlighted by the Me Too and Time’s Up campaigns, but she is unexpectedly vehement on the subject. ‘I am thrilled that it’s happening, and I hope that it doesn’t lose momentum, and people don’t get bored of it,’ she says. ‘People are so used to the norm, and they don’t want to rock the boat – if you put your head above the parapet, you can be seen as difficult. And if a woman’s seen as difficult, then people don’t employ her. Deeply unfair…’

In her own case, she says, the discrimination was subtle yet nevertheless present. ‘I wasn’t preyed on in that way,’ she says, ‘but when you’re doing comedy, the girl never really gets the punchline… that sort of stuff, which is very annoying.

‘I loved being part of it all, and I sort of understood, because I hadn’t written it. But if I had, I’d have shared out the punchlines. At the time, I was just thrilled to be working with really great people; it’s only afterwards that you look back and go, “Oh, hopefully that will change.”’

We talk, too, about equal pay, in the light of the revelation last year that Foy was being paid less than Matt Smith, who played Prince Philip. Is Colman getting as much as her consort Tobias Menzies? ‘I bloody well hope so! It’s not called Philip, it’s called The Crown!’ she expostulates. Still, she admits a little ruefully, ‘as we know, there isn’t equal pay, so Oliver Colman has probably paid off his mortgage, but Olivia hasn’t. The idea is that you get an Oscar and suddenly – boom! You’re a multimillionaire! No –I definitely can’t complain, but I’m nowhere near the realm of paying everything off yet.’

Colman lives in south London with her husband, the writer Ed Sinclair, their three young children, aged between 13 and three, who are ‘deliciously uninterested’ in her work, and two dogs, Alfred Lord Waggyson and Pockets. She tries to keep her home life as normal as possible, and routinely refuses jobs that take her away for any length of time. ‘I get homesick. If it isn’t in the school holidays, so we can all go together, I don’t want to do it. I did a little film in Ohio for two weeks, and that was the longest I’ve been away from Ed in 25 years.’

But the accolades and leading roles have inevitably led to a loss of anonymity, which troubles her, despite the public’s huge and uncomplicated affection. ‘I’m very shy and private,’ she says. ‘I find it very, very difficult to be stared at.’ How does she cope? ‘I don’t go out! I find that fixes it. I was talking to a friend of mine who’s a therapist, and I said, “It’s fine, I just don’t leave the house any more.”As soon as I said it out loud, I realised it sounded quite weird,’ she admits. ‘It’s not what you expect, the other side of it.’

It was in a vain attempt to keep a lid on her ever-growing fame that when she was given a CBE in the Queen’s Birthday Honours list this year, she had it awarded in her married name, Sarah Sinclair. ‘I was thinking it would cause less fuss, and be nice and private,’ she says with a sigh, ‘but now everyone just knows my real name.’

Still, I say, trying to cheer her up, it might mean that she meets her alter ego in the flesh… ‘I imagine she has other stuff to do,’she says wryly. ‘I’m trying not to get my hopes up – but I really want it to be her.’ I bet the feeling is mutual.

Source: harpersbazaar.com – Queen of the Screen: Olivia Colman on fame, fortune and The Crown

Crown Jewel: How Olivia Colman Is Reinventing Superstardom

ROYALS, like successful actors, must make do without some forms of freedom. On the podium or in the camera’s eye, they live in roles that others have provided. Within the court and on red carpets, they’re invested with the harder task of playing themselves. Season three of The Crown, Netflix’s portrait of the rise and reign of Queen Elizabeth II, starts with the monarch contemplating her own aging image on a postage stamp, two enlarged designs from different eras facing her like mirror panes—an unsettling self-encounter echoed at vanity tables and on vintage TVs through the rest of the season. If the series’ first two installments, featuring Claire Foy, played on the theme of duty, the new one, starring Olivia Colman, concerns the pinch of life as a performer. It’s the story of a woman at the peak of self-command who works to excel at all her roles while also—quietly—remaking the norms of the job.

“It’s easy to just go, ‘Well, how hard can being the queen be?’ ” Colman tells me with a chuckle one morning over breakfast at the Ham Yard café in central London. She is dressed in a lightweight black Cos blouse with a shawl collar, a slender gold necklace, a delicate gold watch, and jeans. Friendly with an unexpected layer of self-effacing shyness, she has the disposition of listening even as she talks. “I think it’s really hard,” she says of the queen’s responsibilities. “You can’t just go, ‘I don’t want to do it today.’ ”

The comment is ironic coming from Colman. Long known as an actress of uncanny range—she first emerged as a comic performer on British TV programs such as Rev. (about a hapless vicar) and Peep Show (about feckless flatmates) yet earned early laurels for Tyrannosaur, a searingly bleak drama of trauma and dysfunction—she has emerged as one of Britain’s leading screen artists, an actress who never takes the same shot twice but somehow strikes true every time. “Whatever part she plays seems to fit her like a glove,” says David Tennant, her costar in the wrenching procedural Broadchurch. “She plays everything as if she was born to play it, as if it was written for her.” After Broadchurch, she drew praise again in The Night Manager, playing a pregnant spy while actually pregnant, and then in—well, pretty much every role since. “It’s hard not to cut back to her over and over. In the words of our director Harry Bradbeer, ‘She’s a fucking Ferrari,’ ” says Phoebe Waller-Bridge, in whose show Fleabag Colman plays the protagonist’s arty, pushy, maniacally cheerful stepmother-to-be. “She can be delightfully benign and utterly grotesque at the same time.” “Her talent is somewhat like Mozart’s in Amadeus—and the rest of us just watch like Salieri,” says Peter Morgan, creator of The Crown. “She’s never unprepared, and yet sometimes you find out she’s just learned her lines in the loo five minutes before.”

Colman’s signal moment came this past winter, when she won a best-actress Oscar for her performance in The Favourite as Queen Anne: a childish, heartbroken sovereign with a circle of sycophants and the eye makeup of a nightmare Ronette. Colman—“Collie” to many friends—took to the stage cracking self-deprecating jokes while tearing up, recalling her work as a house cleaner and calling out her weeping writer husband, Ed Sinclair. (“He later said that was the best night of his life, and the kids went, ‘What?’ ” Colman recalls. “ ‘To be fair, watching your wife give birth is very stressful.’ ”) “The person the whole world saw, the way they fell in love with her, not just her performance, that’s who she is,” says Rachel Weisz, a costar nominated for best supporting actress along with Emma Stone, who reports spending parts of the evening in tears at the thrill of seeing someone “so deeply good—and I don’t just mean talent” recognized. (“She is kind of a perfect woman,” Stone explains.) In an industry that trades in illusion and mystique, Colman has helped to announce a down-to-earth age, a moment in which the quality of stardom has begun to shift from the unreachable to the exquisitely human. “There’s no bullshit with her,” Tennant says. “That’s true of her performances, and it’s true of her as a person.”

Today Colman is busier than she’s ever been, and her appetite for new work is so strong that her agents block out calendars with bright colors to make sure she doesn’t double-book herself. “If you’re working, you’re so fucking lucky,” Colman says. “A lot of actors better than me aren’t.” In late summer, she appeared in the creepy snake-populated indie thriller Them That Follow, about a Pentecostal family in Appalachia—a role that required her to perfect a deep-rural American accent. When we meet, she’s just been let loose from production on The Father, a film adaptation of Florian Zeller’s play, starring opposite Anthony Hopkins. She had July off and spent it catching up on her watching (Chernobyl and The Other Two, as well as the reality show First Dates) and taking long walks: a pleasure that fame forces her to forgo in London. Come August, she was back at work on the fourth season of The Crown.

Colman has a double challenge when it comes to Queen Elizabeth. On one hand, she is playing a real, known person whom she’s never spoken to at length. (Colman did receive a more sustained greeting from the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge after winning a BAFTA this year. “I got over-grinny and a bit nervous and was sort of introducing Prince William to everybody,” she says.) On the other, she follows Foy, whom many viewers associate with the role. “I sort of tried to imagine how Claire would do it,” Colman says. “But I’m not actually the queen and I’m not actually Claire Foy.” Unlike the two of them, she also has brown eyes, and contact lenses were attempted, despite what Colman describes as her “very strong eyelids.” “It was basically like an exorcism: ‘Just hold me down and thrust it in!’ ” she recalls. Finally the production resigned itself to a brown-eyed queen. Tobias Menzies, who plays Prince Philip, was not so fortunate in makeup: He had the front of his hairline cropped to mimic a thinning coif. “That’s commitment, isn’t it?” Colman marvels. “Because he’s got to go to Sainsbury’s with a slightly shaved head.”

“She’s a bit obsessed with this,” Menzies tells me dryly, touting her buoyant attitude on set. (“The most influential person on a set is the leader of the company of actors, and Colman is a brilliant leader and a brilliant example,” Morgan says.) In private, Colman’s Queen Elizabeth is chillier than Foy’s, or at least more controlled, as if time and experience have worn down certain of her corners and hardened her core, and the season explores her vexed relationship with members of the royal family. She must command them while requiring their skills and favors to safeguard her success.

Colman’s own professional and artistic ascent is especially striking because it did not happen overnight. The truism in Hollywood has long been that, although a man could emerge into the klieg lights at almost any age, a screen actress who didn’t break through by her mid-30s had lost her chance. For Colman, life as a true movie star didn’t begin until after 40; her coronation holds the promise of a slow, thrilling transformation in the industry. “Definitely, roles are getting more interesting, complicated, and textured,” says Weisz, who, like Colman, has been shining brightest in her 40s. “But women in their 40s are interesting.” Over breakfast, keeping one eye on the clock because the second of her three children has an early dismissal from school, Colman tells me that she doesn’t think she could have made it big as a young actress, nor would she have wanted to. “To be the ingenue and to keep working is rare because once people see you as that, they don’t like the process of aging,” she explains. “Which is fucking ridiculous!” She meets my eyes. “I grew to my place.”

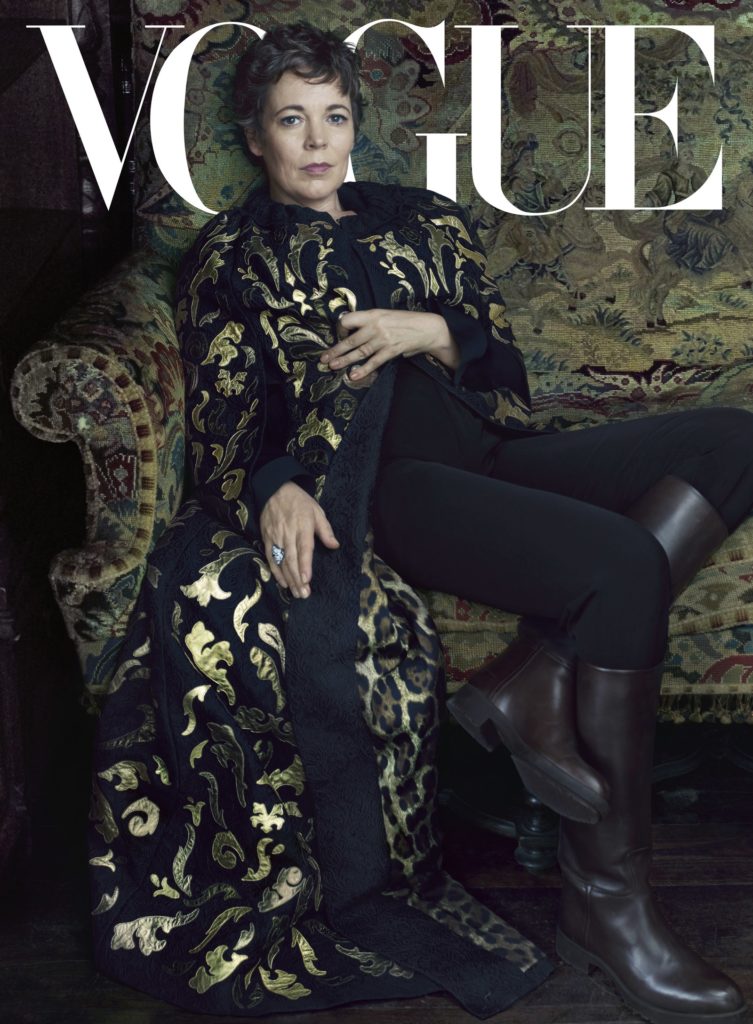

It is customary for Vogue to choose its cover stars from emerging young talent and soaring celebrity leaders. At 45, Colman is a cover woman for a new era: proof of the glamour of slowly and devotedly building one’s life and craft; a reminder that, for a rising generation of powerful women, it is possible to reach success and mastery while remaining honest, patient, healthy, whole. “Everyone shines a little more when she is acting with them,” says Waller-Bridge. “I will always aspire to her level of brilliance, but I’ve been equally inspired by who she is as a person and a professional. Work hard, and be nice to people. And don’t take yourself too seriously. And karaoke. I say those are the secrets to being as close to Olivia Colman as possible. Oh—and be hysterically funny and a genre-defying acting genius.”

COLMAN LIVES IN SOUTH LONDON, in a timeworn, light-filled house that she and Sinclair purchased seven years ago. It is nested in a quiet neighborhood, leafy but not precious, with parks not far away. On summer weekends, neighbors work in their front yards, tending rosebushes and lavender. When I show up, it is the day after the solstice—one of the bright summer Saturdays in London that begin with trees catching the early–morning winds and end with a long, wild, luminous-blue gloaming sky. Sinclair, a silver-haired man with a trim beard, is dressed in cargo shorts and a daddish button-down shirt, untucked; Colman wears a casual charcoal-gray dress. I get on my knees to greet the dogs: Pockets, a Kokoni mix rescued from Cyprus (who leaps to lick my face), and her senior, Alfred, Lord Waggyson, a magisterial terrier-poodle. Sinclair is gathering children out the door, bound for the market.

“Eggs?” he calls.

“I think we have enough,” Colman says, gazing into the refrigerator.

“Sugar?”

The goods are for a barbecue that they are hosting that evening. Sinclair, who does the daily household cooking, will be grillmaster. Colman, a hesitant but dutiful baker, has been charged with dessert. The Colman-Sinclairs are close to their neighbors not just proximally but socially—weekend cookouts, shared playdates for the kids—and the neighbors are in turn protective of the woman they watched grow from a hardworking actress to a global star. “These streets are a lovely community—they really look after you,” Colman says, handing me a mug of tea and leading me to her backyard, which shimmers with summer green. “I think I might never be able to completely leave London, even though I do dream of buggering off to the seaside.”

Colman grew up as a seaside girl, in Norfolk, a windy, tide pool–trimmed idyll on the North Sea. Her mother was a nurse, her father a surveyor who returned to university as an adult student. “We moved houses quite a lot, just for fun,” she says. “I had a nice, outdoorsy childhood—lots of camping, lots of walks on very wet beaches with anoraks.” She had no ambitions to become an actor (“It felt like being a circus performer—if you didn’t do it from childhood, how could you?”) but watched what she could on the family’s black-and-white TV: The Two Ronnies, Knight Rider, Doctor Who. From time to time her grandmother would take her to the movies. “When Bambi’s mummy got done in, I think I had to be taken out of the cinema, and I didn’t go back for years,” she says. “Quite an emotional child. Hard as nails now, obviously.”

On set, Colman is known for deep-diving in and out of character as if flipping a switch. “She just jumps; there’s no, like, ramping in or ramping out,” Weisz says. “Acting is about the speed at which your mind and your imagination keep up, and she’s got this incredibly fast mind.” David Tennant describes Colman’s plunge into the emotion of a character as “infuriatingly, powerfully effortless”: “It can be quite hard to pinpoint where Olivia ends and where her characters begin—she has incredible access.” “Every actor I’ve worked with has some version of getting into character,” Stone says. “She doesn’t even seemingly for a second—like, ever. She’ll go from being ridiculous, making a joke, whatever, to snapping into a woman who’s just had a stroke, is devastated, and is gout-afflicted.” Colman calls herself “emotional, but also emotionally stable”: tossed around by the turbulence of each moment, but placidly on course for the long journey. She suggests that this style of being makes acting less psychically corrosive than it might otherwise be. “Some people, if they’re playing a very emotional part, it can take hold of them a bit, and I don’t have that,” she says. “I feel it very much in the moment. But as soon as they say, ‘Cut’: Ahh. It’s cathartic. I actually feel much lighter, having had a good cry.”

In high school, Colman struggled to take pride in her appearance. “I look up pictures of myself as a teenager, and I think I was gorgeous. But I didn’t feel that,” she says. “All those little comments through those precious years can have long-lasting negative effects. You see images of a perfect person and say, ‘I can never be that.’ ” Age and wisdom helped, as did the confidence she found in acting and in her marriage. “Over the years, pounds have gone on, and my body has changed; I’ve had children,” she says. “If someone doesn’t like me because of the size of my bum, they can fuck off. Because I’m quite a nice person to be with, actually.” Even so, she still works to feel comfortable with her body and—despite being an international star and a Vogue cover—sometimes finds herself glancing away from mirrors.

“Once I was in a steam room and there were these two women, big women, who sat there, hot and sweaty, so beautiful—I felt like they were almost goddesses,” she recalls. “I want that confidence.” Getting there is an ongoing process. She eats healthfully (vegetarian Monday to Friday, fish and chicken on the weekends) but doesn’t lose sleep or happiness over it: Food is one of life’s pleasures. Netflix set her up with a trainer (ironically or not, playing the queen requires vigorous form), but she is not one of those actors who hit the gym at 5 a.m.: If sacrifice of time and sleep is in order, let it be for family. Most of all, she tries to remember that beauty is mostly an assured way of being in the world. “I just always want to tell my children that they’re beautiful,” she says.

We are sitting with our tea on a bench in the corner of Colman’s backyard: a large rectangle of rich-green lawn with a treehouse that Sinclair built for the kids. A cricket bat has been abandoned in the grass; some toys and a scooter are upended underneath a gnarled birch. Colman apologizes for the disorder and then, after a moment of reflection, unapologizes. “Although I get fed up with the mess and things, it’s exactly what I always wanted,” she admits. She had dreamed of a family since she was 11 years old, but in part because she and Sinclair were in no great rush—they had their first child when Colman was in her 30s, after more than a decade of partnership—she thinks that she was able to savor the experience of motherhood fully when it came. “I wanted it slightly anarchic, noisy, grass with toys on it,” she says.

Colman and Sinclair met as young actors in Cambridge: He was at the university, and she was living in the town, working as a house cleaner, a job she loved. “It was such a position of trust,” she says; she took great pleasure in making a house beautiful. She had enrolled in the teachers-training program at Homerton College, Cambridge, but soon dropped out. (“I was rubbish at it.”) Cleaning houses let her stay in town, crashing lectures, and, on a whim, auditioning for student–theater productions. She was not a young woman in a hurry. “It was very important to me in my late teens and early 20s to have fun—it’s a great time to have fun,” she says. Her auditioning led her into the Cambridge University Footlights, a dramatic club that she had never heard of, despite its reputation for being a hatchery for generations of British comedians—Hugh Laurie, Emma Thompson, John Oliver, and several stars in Monty Python, to name just a few. Two members at the time, David Mitchell and Robert Webb, recognized her comic genius and worked with her often. (Much later, Mitchell and Webb featured in Peep Show, her first big break in Britain.) By then, she had met the inspiring young actor Ed Sinclair.

“I saw Ed, fell in love, and lost it completely,” she says. “All I could see was him.”

Colman worked as a temp and cleaner in London while Sinclair finished his Cambridge degree; when he went on to the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, she followed him, still smitten, assuming that she wasn’t drama-school material herself. As he brought friends by for dinner, though, Colman found she loved hearing about their work at school. “They’d eat and talk about the theater, and I went, ‘This is where I should be—I want to be part of it,’ ” she says. The next year, she applied and, to her surprise, got in.

It has become an irresistible irony that Colman, the house cleaner who tagged along to Bristol with her drama-school boyfriend, is now the family’s star actor and its lead breadwinner, too. (Sinclair has acted professionally but works now chiefly as a writer.) Colleagues of hers all marvel at her capacity to build her career around the life she found it important to live. In a notoriously peripatetic profession, Colman has remained close to home; Them That Follow, filmed in Ohio, was her first production in America, and her two weeks on set was the longest she has spent away from her family. “I get homesick. I don’t sleep well without Ed, and I miss the kids.” In London, she is able to spend the day at work, then return home in the evening to her family and neighbors. (Her kids, she says, have zero interest in Mom’s job; they prefer math, science, and crafts.)

It’s partly on account of her family that Colman does less theater than she used to—a loss in the eyes of many. (Weisz: “I saw her in Mosquitoes at the National Theatre in London, and she kind of brought the house down. We were crying in our seats.”) A theatrical run, which provides off-time during the day, is great when there’s a baby in the house, Colman explains, but now that her kids span between kindergarten age and the early teens, it keeps her from tucking them into bed—a ritual she cherishes.

Also, her theater nerves are not what they once were. “I get genuinely terrified: panic attack, dry mouth,” she says. “The fear manifested itself as adrenaline before, but now it’s just fear.” For a long time, the red carpet inspired similar terror. “A lot of people take on a pretend persona, but I’m crippled by it. I feel embarrassed,” she says. “A breakthrough for me was at the Venice Film Festival, wearing Stella McCartney”—a glorious flowing ensemble with a trailing cape. “I felt, I can do this, I can do this,” she says. “I’d always used clothes as a sort of mask. I discovered that they can make you feel strong and powerful.” In other words, more truly oneself.

Colman wants to make meringues for her barbecue guests and suggests that I “help”—a term I place in quotation marks to preserve its intended spirit. (My confidence as a baker roughly correlates to Colman’s on the red carpet; my record is worse.) First, though, comes fortification, which is to say more tea. Colman pumps a gurgling spurt into my cup from a boiling-water faucet arcing over the sink. She takes milk from the refrigerator and notes a pitcher of lemonade that her children made earlier that day. “It looks like a urine sample, but it is actually very delicious,” she insists. She begins splashing milk into my mug, then peers at it dubiously. “I’ve made that very pissy—is it too weak?”

“I’ve had a lot already,” I say. Behind me, the kitchen table is covered with Legos and colored pencils, and children’s drawings are stuck to the wall, near a narrow shelf of cookbooks. Colman is whooshing through an iPad, brow furrowed. It emerges that she has never made a meringue before. It emerges that neither of us has ever made a meringue before.

“It’s two ingredients. How hard could it be?” she asks, still reading. “Oh—‘Difficulty level: showing off.’ ” She pauses for a moment and our eyes meet; Colman gives a little shrug. “It can’t be that hard,” she says. She heats the oven, opens a carton of eggs, and begins jogging a yolk back and forth between two bits of shell.

“It’s a bit like snot, isn’t it?” she exults. She casts away the yolk with a flourish. “Nothing can go wrong now.” Colman looks quizzically into the bowl. “I’ve lost count,” she says. “Was that four?”

“Four or five?”

“Let’s pretend it’s four,” Colman says, cracking open another egg. She consults the iPad. “ ‘With your mixer still running, gradually add the sugar and a pinch of sea salt.’” An immersion blender is produced. She hands me a cup of sugar. “I’m gonna keep whizzing while you put that in!”

Alfred, Lord Waggyson, is watching us from as far away as possible, curled up at the head of a sofa near the front windows of the house. I am not so vexed: There is something fun about working with Colman, even on this small and foamy project, and I start to understand why David Tennant recalls “laughing more than we should have done” while making even the grim, bleak Broadchurch. “It’s obviously getting so thick,” she says suddenly, nervously peering into the bowl. “I’ve about over-whisked it.”

“I don’t think over-,” I say.

She checks the instructions. “ ‘Seven to eight minutes until the meringue is white, glossy, and smooth. If it feels grainy, whisk for a little bit longer, being careful not to let the meringue collapse.’ ”

We stare at our bowl for a while. The egg whites sit there in a foamy lump. “I don’t think it’s collapsed,” I finally say. “It looks quite . . . present.”

Colman sticks in a finger. “It doesn’t feel grainy,” she says.

“It does look glossy and smooth,” I say.

Colman spreads a sheet of parchment on a baking pan and pours the mixture into two gigantic dollops. “Wish it good luck,” she exclaims and carefully ferries the tray into the oven.

I ask her then whether she doesn’t marvel sometimes at the course her life has taken: Two decades ago, she was cleaning houses, and yet, unlike with the mythical waitress turned starlet, the accrual of magic in her life happened over years, touching work and family alike.

“It’s amazing, isn’t it? Ed and I do sometimes go, Look. We’re still together. We’ve got a family. I’m working,” she says. “Appreciating what’s happening when it’s happening, I think, is quite good and healthy,” she says. “When the kids do badly with exams or something, I want them to know that in the grand scheme of things, it doesn’t matter. Life’s that big.” She smiles and gives me a warm, bashful look. “I just want to try to keep them buoyant and happy. And seeing life as—potentially—beautiful,” she says.

Source: vogue.com – Crown Jewel: How Olivia Colman Is Reinventing Superstardom

The Crown’s Olivia Colman on attempting Queen’s accent: ‘Every syllable in every word, you’ve got it wrong’

She has an Oscar, a Bafta, a CBE and – if modesty allowed – files full of rave reviews.

If Olivia Colman, actor and current national sweetheart, needed to be brought back down to Earth, it seems a day of playing the Queen might do the trick.

Colman, who is taking over from Claire Foy in the new series of The Crown, has admitted her attempts to mimic the Queen’s voice with the show’s “amazing” voice department had initially fallen flat.

“Once you start going through it, you realise that every syllable in every word…you’ve got it wrong,” she said.

Following in the footsteps of Foy on the Netflix show, she joked, was therefore “horrendous”, adding: “Everyone loves Claire Foy, so I have got the worst job in the world at the moment.”

Of her role playing one of the world’s most famous women, she said: “It’s the same as any classical play you do — everyone will have already played that part before.

“The first week, I did feel myself trying to do Claire impressions. ‘What would she have done?’”

Colman has joined the third series of The Crown along with an entirely new main cast, with Tobias Menzies playing the Duke of Edinburgh, Helena Bonham Carter as Princess Margaret, Josh O’Connor as Prince Charles and Emerald Fennell as the then-Camilla Parker Bowles.

Future series, to be cast as the characters age, could see Dame Helen Mirren return to the role of Queen for Netflix as writer Peter Morgan told Entertainment Weekly she “loves the show”.

The third series, broadcast from November 17, will begin in 1964 and cover events including the unmasking of the Queen’s art adviser Anthony Blunt as a Soviet spy, the Aberfan disaster and the moon landings.

Asked whether viewers would accept the new cast, Morgan said: “It’s a bit like changing contact lenses. I think it takes you about five minutes to get used to it.”

The plot will move away from the marriage of the Queen and Prince Philip, actors said, with Colman telling the US magazine: “Between them they’re more settled, aren’t they? Slightly more mature, they’ve got all of their children now. It’s more external factors that are bothersome.”

Scandal will instead focus on Princess Margaret and Lord Snowden, played by Ben Daniels.

“They’re such extraordinary people,” said Daniels, “Completely addicted to each other. Even right up until the minute they were getting divorced, they still had a really strong physical relationship.

“People often said that it was like foreplay for them, having a big row. They would have these huge rows and then amazing sex.”

The full interview is available in Entertainment Weekly.

Olivia Colman: People power has given actresses more roles over 40

Olivia Colman is “thrilled” that there are now more roles for actresses in their forties, and believes audience power is behind the change.

The star, 45, won an Oscar in February for playing Queen Anne in The Favourite, and many of her most acclaimed roles — including in Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag, BBC’s The Night Manager and ITV’s Broadchurch — have come later in her career.

Colman said she was “grateful” that she has had to work for her success, saying: “It’s been a long, slow road, but I feel very blessed.

“I’ve always worked — apart from the first couple of years, but I’m also grateful for that because it teaches you to push.”

She added: “There are more roles now for women in their forties, and the roles get more interesting because they lean on that experience. It used to be over once you’re passed the ingenue thing, but those voices are being heard now.

“People go, ‘I want to see myself depicted [on screen], because I’m the one in charge of the remote control and I’m paying the bills.’

“Love doesn’t just belong to people in their twenties. I’m thrilled those parts have come around for me.”

Colman also revealed that she often does not conduct in-depth research when preparing for a part. She said: “Otherwise, I think, you’re throwing too much in. The work has been done for you if it’s a good writer. I think, ‘What could I possibly find out that the script hasn’t already told me?’ ”

Source: standard.co.uk – Olivia Colman: People power has given actresses more roles over 40

Olivia Colman accidentally slips into Cockney accent while filming The Crown

Olivia Colman has revealed that she accidentally falls into a Cockney accent while playing Queen Elizabeth II on the set of The Crown.

The Oscar-winning actress has taken over the royal mantle from Claire Foy for the Netflix hit’s third and fourth season, and admitted that the show’s voice coaches provide indispensable assistance when she goes “off in the wrong direction.”

“Playing the Queen is not all me. You have an awful lot of assistance,” she told Metro.

“There is an amazing voice department who are always there and who whisper vowel sounds and things because I keep going off.

“Weirdly I feel like her voice is quite close to Cockney, which is quite hard to explain, and I can feel myself going off in the wrong direction.”

The 45-year-old went on to reveal that her “amazing movement coach Polly” has helped her out with the intricacies of royal protocol, giving her “little tricks to remember how you are meant to stand.”

She explained that she has been watching “lots” of old videos of the Queen in order to prepare for the role, telling the paper that “the research department search for all the footage there has been and send it you.”

Colman will be joined by a new cast of on-screen royals as the show’s action moves into the 60s and 70s, with Helena Bonham Carter set to play the Queen’s younger sister Princess Margaret and Tobias Menzies taking over from Matt Smith as Prince Philip.

Source: standard.co.uk – Olivia Colman accidentally slips into Cockney accent while filming The Crown

A Conversation With the Oscar-Nominated Olivia Colman, the Star of The Favourite

It takes a lot for a film to be nominated for even one Academy Award. But to be nominated for 10? Now, that’s a feat. That’s what Greek director Yorgos Lanthimos achieved with period drama The Favourite, which premieres exclusively in Ayala cinemas today, February 20.

It might have the huge hair, the big dresses, and the ornate castles, but The Favouriteisn’t your typical period drama—not when Lanthimos is the mind behind The Lobster, a black comedy film where people have 45 days to find a soulmate before turning into an animal. He also helmed Dogtooth, a drama about a couple who try to keep their children as isolated from the outside world as possible.

The Favourite stars celebrated English actress Olivia Colman as Queen Anne, the sick and spoiled royal who leaves it to her aide Sarah Churchill (Rachel Weisz) to handle the government side of her rule. Queen Anne enjoys being Her Royal Highness, while Sarah does the dirty work of her duties. But when Sarah’s cousin Abigail (Emma Stone) turns up in search of a job, they start going head-to-head to become Queen Anne’s, well, favorite. Needless to say, things start getting crazy. The film also starsNicholas Hoult and Joe Alwyn.

The film is a reunion for Lanthimos and The Lobster co-stars Colman and Weisz. Colman is most known from the series Broadchurch and the film Tyrannosaur but if you’re not familiar with her yet, you might want to catch her as Queen Elizabeth II in the upcoming season of The Crown. She’s long been known as one of the best English actresses both on TV and film, which is why her work on The Favourite has earned her many nominations and awards. She won Best Actress in a Leading Role from the British Acedemy Film Awards and she’s also up for Best Actress at the upcoming Academy Awards.

Before you find out for yourself what makes The Favourite an awards-show favorite, Colman shares about her experience working on the film in this exlcusive interview. She talks about the process of preparing for her role, working with Lanthimos, her “bitches” and now-lifelong-friends Weisz and Stone, and finally making it big on the international stage.

How much did you know of the history behind The Favourite?

Not a thing. It’s amazing, isn’t it? The film is surprisingly accurate, because it does feel so far away from what we know to be period drama. You think it has got to be made up. But so much is correct.

I just love the way Yorgos has done it. It’s not the way you think a period drama is going to be. Everything he did with the shots; the fish-eye lenses. It’s all so different from any period movie you’ve seen before.

But, in a way, it’s less about the history of the piece as it as about this woman who has lost all these children, and her love for these other women. It’s less about holding yourself in a certain way, or getting used to the way people speak in period dramas. These are real people, and you can kind of smell them. They’re a bit grubby and unwashed. I was actually a little nervous about it being a period drama, but it just isn’t that.

How does the process of filmmaking begin?

It’s all written down. Yorgos is less interested in big discussions. When a script is done, he says, throw yourself into that. You don’t really need to know all the things around it. This was written so beautifully. It’s obvious, the moments when she’s being a cow, when she’s being manipulative, or she’s bored and she’s childish. So we just let rip and run with it.

What did you like about Queen Anne when you read the script?

The fact that she displays every emotion, good and bad. Every trait. It’s great to play somebody who does so many things. It’s a challenge and it’s fun, so it was a no-brainer. I really wanted to play her. It’s a gift, really, to play all these things.

Did you find it personally helpful to dig into any research?

Only afterwards, which is what I often do. Otherwise, I think, you’re throwing too much in. The work has been done for you if it’s a good writer. I think, What could I possibly find out that the script hasn’t already told me? It’s there in the scenes between Anne, Sarah, and Abigail. You feel Anne’s frustration in the film. I wouldn’t want her job. You can’t really trust that anybody genuinely likes you. Everyone is just waiting to get their own needs met at all times, and you believe that of Sarah, but you find out she might be the only one genuinely there for Anne. She might be the love of her life.

You’ve worked with Rachel before, on The Lobster, which Yorgos also directed.

Yes. Rachel and I only had one scene in The Lobster, where she was instrumental in tying me up. I remember that we got on very well, very quickly. She’s a lovely, fun person. Emma, I’d never met. Yorgos held a lovely little dinner, for us to meet each other, and she came in full of energy and you instantly think, Oh, I’m going to like you. We will be friends for life, I think, the three of us.

Rachel had done a lot of theater and physical theater as a young woman, and Yorgos loves to rehearse in a physical way. So it was so much fun to do that with her. She was gung-ho, throwing herself into it, and so brave. It’s a joy to work with someone like that, because once one person has gone for it, it encourages the rest of you to go, “Great, let’s all jump in.” There was no embarrassment here at all.

Yorgos seems particularly interested in awkwardness and embarrassment, and a lot of this film deals with those things.

I think that’s true. I think that comes through the rehearsal process, especially for The Favourite. He comes from theatre too, so we’d play classic theatre trust games and things like that. You become very close, and that really helps. It’s not like you’re meeting on Day One, “How do you do?” And then you’re shooting a sex scene. That’s hideous.

Also Yorgos has no embarrassment, and it always starts from the top. He’s a disarmingly big, gentle bear. He’s lovely, warm, friendly. I only once saw him roll his eyes and go, “Ugh,” and it was when I asked him what happened to the girl at the end of Dogtooth [laughs]. He went, “Ah, I don’t know. The film is finished, make your own mind up.” He puts it all up on screen and then it’s up to you to decide.

You want to impress Yorgos. He wants you to be human, and real, so you go for it. You’re snotty and spitting. I wanted him to think, “Oh, good. She’s willing to be disgusting.” I think we all felt that. We always want to see him do a little smile and nod at the end of a scene.

You say it’s not a traditional period drama, but you do get to wear some spectacular costumes in the film. Did you enjoy that aspect of it?

I loved them. It’s Sandy Powell [Powell is a three-time Academy Award winner and an 11-time nominee]. The Queen’s clothes were hilarious. I spent most of the film in a nightie, so I was fine. Poor old Emma and Rachel were a little more tailored. I was eating cake and pizza and trying to keep as fat as possible, while wearing a big, flowing nightie.

Yorgos encourages his team: “Come on. Surprise me. Do something bold.” So you have Nadia Stacey, the makeup designer, coming up with such fun looks. In the ball scene, you may not even notice them, but instead of those heart-shaped beauty marks you see, she came up with stencils of horses and carriages. Taking something we’ve seen before, but making it bonkers. Sandy was the same way. A flash of red, or the servants wearing denim. There’s so much to see from all these different inputs, and Yorgos gave everyone the courage and free rein to have fun. Everyone was told, “Do it. Nothing is too silly.”

You’ve been on British screens for a while, and now you’re enjoying international success. How hard fought has that been?

It’s been a long, slow road, but I feel very blessed. I’ve always worked. Apart from the first couple of years, I’m also grateful for that because it teaches you to push. I suppose you come into your own. There are more roles now for women in their 40s, and the roles get more interesting because they lean on that experience. It used to be over once you’re passed the ingenue thing, but those voices are being heard now. People go, “I want to see myself depicted, because I’m the one in charge of the remote control and I’m paying the bills.” Love doesn’t just belong to people in their 20s. I’m thrilled those parts have come around for me.

Source: spot.ph – A Conversation With the Oscar-Nominated Olivia Colman, the Star of The Favourite